Robert "Cyclona" Legorreta

- Artist Robert Legoretta

- Robert's Art

- Contributor Vivian Acosta

“I am perception, perceive me as you will.”-Robert Cyclona Legorreta

Robert Legorreta was born in El Paso, Texas, in 1952. After moving to East Los Angeles, Legorreta began performing (at age 14) and parading in various costumes on Whittier Boulevard. In an interview with Jennifer Flores Sternad, Legorreta confesses having donned himself with women clothing, fake breasts, makeup, and dressed “very female...kind of like drag.” He proclaims that he would taunt and tease the drunk men and “all the cholos and the gang members and all these crazy guys who were stoned out of their brains.” Edmundo Meza was a colleague, and also an artist that often collaborated with Legorreta in East LA. They created provocative performances and called themselves “psychedelic glitter queens.” Legorreta quickly realized that his performances were causing a major attraction in his community. The public began to inquire about his sexuality, and calling him queer. Soon thereafter, Legorreta premiered in first play Caca-Roaches Have No Friends, and also began to establish his character Cyclona.

In a video directed by Krystal Leach de Amante, Legorreta states that the character “Cyclona” developed between the years 1966 and 1969. Despite being threatened and in some cases physically assaulted by bystanders that felt offended by Legorreta’s street performances, he continued to challenge the norms of society encompassing gender, race, and sexuality. Legorreta’s character Cyclona sought to bring art to life by countering gender representations and stereotypes.

In his book The Fire of Life The Robert Legorreta-Cyclona Collection, Robb Hernandez states that the civil rights struggle left a large impression on Legorreta's performances, and thus allowed his artistry to grow into an advocacy for social justice in East L.A. The turmoil of political activism, the Chicano Movement, and Antiwar Movements were all topics that eventually structured the basis of Legorreta’s character, Cyclona.

The Chicano Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s played a crucial role in the execution of Legorreta’s performances, which ultimately allowed his art to flourish in activism. Legorreta had been an active student protester against the racism that was being ignored at his home school, Garfield High School. He endured the institutionalized racism, which was an early sign of the issues that emerged during the Chicano Blowouts of 1968.

This is a video called The Fire Of Life, which was directed and edited by Krystal Leach de Amante. In this video Robert Cyclona Legorreta discusses his first performances and the development of his character “Cyclona.” Legorreta’s first performances as a teen primarily took place during Halloween, and his response for this was “because of family, that’s the only way you could get away with it [sic].” I found this particular response interesting, because Legorreta wasn’t afraid to express himself in public, despite their insults.

I sense that Legorreta was embarrassed of revealing these political statements through performance art to his family members. He believed Cyclona to be a political character, especially since his performances were considered daring actions. Legorreta states that the only other types of performances that were prevalent during the 1960s were drag queens; therefore he sought to bring art to life on stage and create a conversation among the people.

He argued that society has become deeply embroiled in war, and needs to become unified. In order to bring change individuals must take advantage of the law, such as voting, and activism. The movie also features a small clip of a performance called Death Becomes Life, Life Becomes? This performance is described more thoroughly at the bottom of this page.

(figure 1)

(figure 2)

(figure 3)

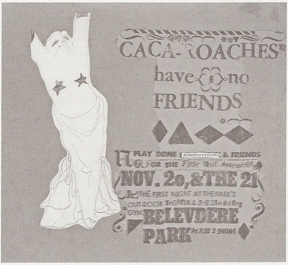

Figure 1 is a flyer of Cyclona's first play written by Asco artist "Gronk," and entitled Caca-Roaches Have No Friends. The event took place on November 20, 1969 at Belvedere Park in East Los Angeles. Although the event was publicized in a manner that welcomed families and their children, both Cyclona and collaborator Edmundo Meza had prepared something different.

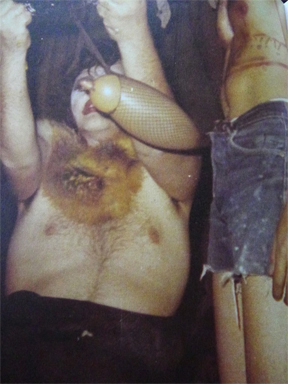

Cyclona wore exaggerating make-up, which is seen in both Figure 2 and 3, by painting his face white with black eye shadow, red lipstick, and long furry sideburns. The audiences were shocked by Cyclona’s appearance. Despite Legorreta’s overly effeminate style, author Robb Hernandez writes that “Cyclona’s meaning is not about drag queen, cross-dresser, transexual,” which are labels given by cultural critics. Instead, it is “determined by the spectator’s reception of Cyclona’s ‘mind-blending’ spectacularity,” which is evident in the renowned “cock scene” of Caca-Roaches Have No Friends. During this part of the performance Cyclona was joined by another man whose shorts had been attached with a long balloon and two eggs. As reported in Hernandez’s book The Fire Of Life: Robert Legorreta- Cyclona Collection, Cyclona pulled a fishnet garment over the phallic object, pierced the balloon with his teeth until it popped, and the eggs fell to the ground.

In an interview with Jennifer Flores Sternad, Legorreta described "this as a protest against gerontocracy and cites it as the impetus for the audience’s violent reaction to the play [sic].” Cyclona’s protest against gerontocracy revealed the extent to which people are governed in society. The play is a prime example of how individuals should not be limited to the restrictions of conventions but rather open to any degree of expression.

(figure 4)

(figure 5)

Both figures 4 and 5, display Cyclona in her wardrobe for a performance titled Death Becomes Life, Life Becomes?. The fundraiser event was created in dedication to Dia De Los Muertos, that took place on November 1, 1992, at the Catch One Disco. Artist and collaborator Angelo Perez, dressed in a skeletal body suit, assisted Cyclona during the performance. Cyclona's wardrobe was stitched together from other costumes and layered with various patterns and designs. The dress was laced with multiple different kinds of beads.

Cyclona also wore a multi-layer hat which included feathers and other ornaments. Figure 5 displays a “fire god image” which was created by Chicano artist Roberto Gutiérrez, and appeared on the back of Cyclona's wardrobe. In Robb Hernandez’s book The Fire Of Life: Robert Legorreta- Cyclona Collection, Cyclona was creating an "illusion of a divine leader unleashing a sanctimonious death ritual."

Natural sounds such as wind, thunder, and rain played in the background while Cyclona glided across the stage cleansing the bad spirits with a staff. Hernandez discusses that Cyclona’s performance “condemned a Reagan-Bush White House for its politics of blood,” while his audiences were “silent witnesses to the government’s victimization of the people living with AIDS, people of color, women, and working poor.” The performance commemorated all the underrepresented individuals, and operated as a form of liberation from their oppressors.

My name is Vivian Estela Acosta. I was born on August 4, 1992, in Inglewood, California. I am the second oldest of four siblings. I'm a third year at the University of California, Los Angeles. I'm currently majoring in Fine Arts with two minors in Chicana/o Studies and Urban and Regional Studies.

Having attended a Title 1 high school, in which the United States Department of Education proffers supplemental funding to meet the needs of low-incomes students, I never had the opportunity to take any studios before I entered the University. My high school only had one art class with a main focus in drawing. Unlike a great number of students at the University, whose familiarity with studios surpassed my knowledge, I felt alienated.

My experience as an underprivileged individual, attending an institution whose goal is to “teach art” is a powerful matter. As an artist I don’t feel like I was taught about art. I believe that at UCLA I am expected to explore different mediums to convey my perception of the world. As a Fine Art major I always questioned why art was perceived as something disconnected from the world, and aesthetically critiqued.

It wasn’t until I met muralist and social activist Judith F. Baca. Baca made me realize how art had become an individualistic activity, and how in Western society the artist and their artwork are acknowledged as a private relationship. Ultimately this is an issue I wish to explore in the future. Art should be inclusive, and should not create a boundary for underprivileged individuals, but rather allow for their embracement of life and optimism.